Manuscript no.: PC-109

Low-lying Energy Ordering of Singlet and Triplet Excited States in s-indacene, Pentalene, Cyclobutadiene Derivatives in Singlet Fission : A Model Exact and Density Matrix Renormalization Group Study

a Department of Chemical Sciences, IISER Kolkata Mohanpur-741246, India

b Center for Advanced Functional Materials, IISER Kolkata Mohanpur-741246, India

E-mail: rp21rs061@iiserkol.ac.in

Specific molecules show an optimal energy configuration of singlet and triplet states due to the combination of anti-aromatic and aromatic components alongside bulky substituents. They exhibit long-lasting triplet excitons and have appropriate structural modifications that make them particularly appealing for use in organic electronics and photovoltaics that rely on singlet fission (SF). We effectively utilized exact diagonalization along with the Symmetrized Density Matrix Renormalization Group (SDMRG) approach for the model Pariser–Parr–Pople (PPP) Hamiltonian to forecast low-lying excited states, contrasting them with TDDFT, EOM-CCSD, CASPT2, and DMRG-SCF results.

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic molecules are valued for stability from Hückel’s 4n+2 rule, while anti-aromatic 4n systems, though unstable, enable tuning of reactivity and optoelectronic properties.1 Fusing aromatic and anti-aromatic units modifies bond alternation, conductivity, and excited-state order, useful in photovoltaics.2 Singlet fission (SF), a spin-allowed process, converts one singlet into two triplets, reducing thermalization losses and exceeding the Shockley–Queisser limit.3 Efficient SF requires E(S1) ≥ 2E(T1), E(T2) > 2E(T1), and T1 ≈ 1.1 eV for silicon.4 Anti-aromatic units like s-indacene and pentalene show potential but low stability and E(T1) is very low; benzannelation or substitution improves performance.5 Systems fused with cyclobutadiene, pentalene, or s-indacene exhibit tunable ordering. Accurate excited-state prediction needs correlated methods beyond DFT; we apply PPP Hamiltonian with exact diagonalization and SDMRG, supported by EOM-CCSD, CASPT2 and DMRG-SCF.6 Results agree with experiments, guiding efficient SF chromophore design.

2. Experimental Section

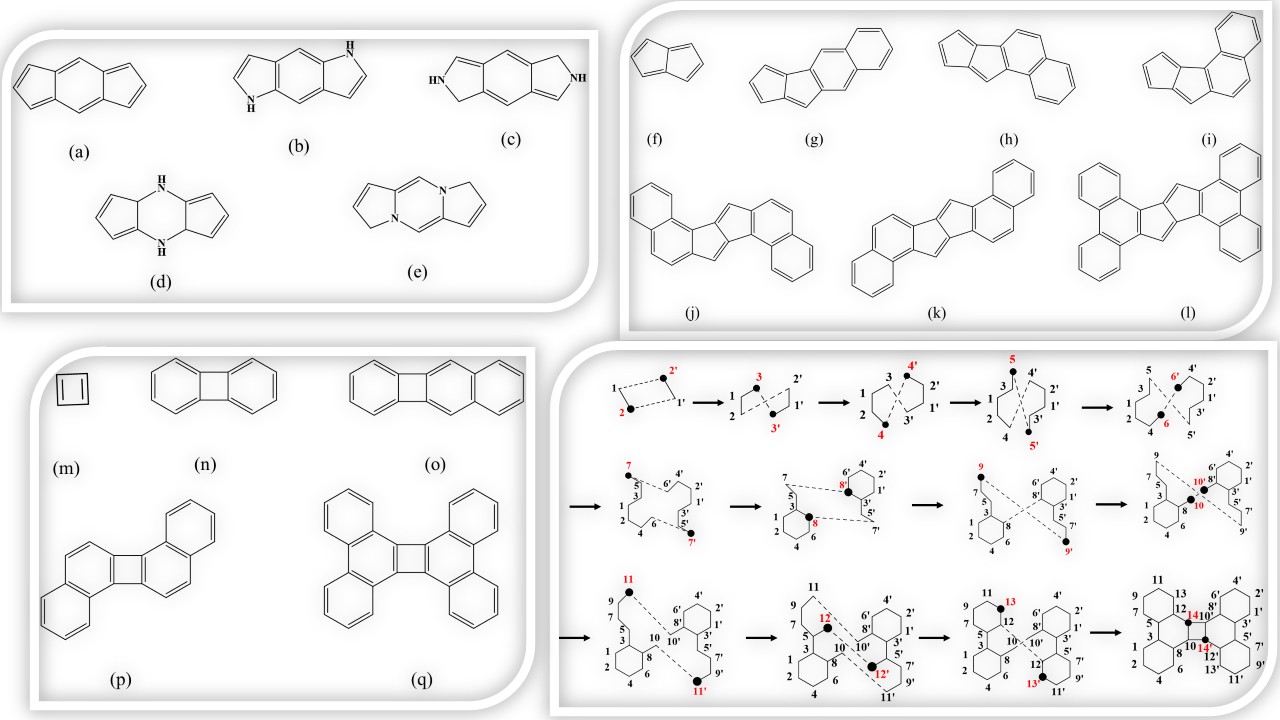

All conjugated molecules (Fig. 1) were optimized with DFT (B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)) in Gaussian09, and minima verified by vibrational analysis. Ground and low-lying excited states were computed with a correlated Pariser–Parr–Pople (PPP) Hamiltonian7 including on-site Hubbard and long-range Coulomb terms (Ohno scheme). Transfer integrals were distance-dependent; orbital energies for heteroatoms followed literature.7 Spin parity symmetry reduced computational cost. For ≤16 carbons, low-lying excited states were obtained via exact diagonalization in a diagrammatic valence bond (DVB) basis using Rettrup’s algorithm, yielding full CI solutions. EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ was also applied (ORCA). For larger systems (>16 carbons), we used Symmetrized DMRG (SDMRG) with spin and C2 symmetry, a cutoff of 600 states, and finite-size sweeps. Vertical excitations were further computed by state-average DMRG-SCF/cc-pVDZ (PySCF/DMRG-BLOCK). Spin–orbit coupling constants <T1∣HSOC∣S0> were evaluated with B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) using PySOC/MolSOC.

Figure 1. Schematic diagrams of molecules studied and representation of molecule (q) using SDMRG scheme beginning from four carbon atoms

3. Results & Discussion

All conjugated molecules (Fig. 1) were optimized with DFT (B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)) in Gaussian09, and minima verified by vibrational analysis. Ground and low-lying excited states were computed with a correlated Pariser–Parr–Pople (PPP) Hamiltonian7 including on-site Hubbard and long-range Coulomb terms (Ohno scheme). Transfer integrals were distance-dependent; orbital energies for heteroatoms followed literature.7 Spin parity symmetry reduced computational cost. For ≤16 carbons, low-lying excited states were obtained via exact diagonalization in a diagrammatic valence bond (DVB) basis using Rettrup’s algorithm, yielding full CI solutions. EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ was also applied (ORCA). For larger systems (>16 carbons), we used Symmetrized DMRG (SDMRG) with spin and C2 symmetry, a cutoff of 600 states, and finite-size sweeps. Vertical excitations were further computed by state-average DMRG-SCF/cc-pVDZ (PySCF/DMRG-BLOCK). Spin–orbit coupling constants <T1∣HSOC∣S0> were evaluated with B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) using PySOC/MolSOC.

To validate SDMRG, ground-state energies of >16-carbon systems were benchmarked in the Hückel noninteracting limit and compared with exact HMO results. With a cutoff of 600 density matrix eigenvector (DMEV) states, SDMRG errors were <0.5%, confirming accuracy. Excitation energies are even more reliable in correlated systems. Alongside the PPP Hamiltonian, we employed ab-initio EOM-CCSD, TDDFT, and DMRG-SCF. For small molecules (b–e), PPP reproduced experimental absorptions better than TDDFT, which often overestimates (e.g., b, c, e). Molecule (c) agreed more with EOM-CCSD, while (e) gave PPP (2.62 eV) vs. experiment (2.42 eV). Molecules (g, i) showed solution-phase red shifts relative to isolated-molecule theory. CASPT2 calculations further supported PPP, e.g., (g): CAS(8πe,6πo) = 2.46 eV vs. 2.30 eV experiment. For larger systems (j–q), PPP and SDMRG results matched TDDFT, DMRG-SCF, and experiment, e.g., (k): 2.31 eV vs. 2.30 eV; (p): 3.07 eV vs. 3.03 eV.

Energy ordering analysis revealed that s-indacene (a) has too low T1 for efficient SF. Substitution improves properties: molecule (c) has T1 ≈ 1.28 eV, close to the Si bandgap, and correct ordering (S1–2T1 = 0.50 eV). Molecule (e) also satisfies the first SF criterion (exoergic S1–2T1 = 0.50 eV) with long-lived triplets, though T2 ordering is less ideal. Pentalene (f) shows large energy loss despite correct conditions, while benzannelated derivatives (g–i) are better: T1 ≈ 1.1 eV, favorable for Si cells. Larger fused systems (j–l) show mixed behavior: (j) is promising (T1 = 1.13 eV), but (k, l) have too low T1.

Cyclobutadiene (m) has suitable ordering but is unstable. Benzannelated analogues (n–q) are more stable: (n, o) show undesired high S1, while (p) stands out with S1–2T1 = 0.55 eV and T1 ≈ 1.26 eV, meeting SF criteria and matching experiment (3.07 vs. 3.03 eV). Molecule (q) is less suitable due to low T1.

Spin–orbit coupling (SOC) constants for the most favorable SF candidates (c, e, g–i, j, p) are very weak (<10 cm⁻¹), indicating negligible intersystem crossing (ISC).

4. References

- R. Breslow, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 1968 (7), 565-570.

- O. El Bakouri, J.R. Smith and H. Ottosson, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2020 (142), 5602-5617.

- M. B. Smith and J. Michl, Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 2013 (64), 361-386.

- J. C. Johnson, X. Chen, G. Rana, D. Popović, D. E. David, A. J. Nozik, M. A. Ratner and J. Michl, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2006 (128), 16546-16553.

- H. Hopf, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2013 (52), 12224-12226.

- G. Giri, Y.A. Pati and S. Ramasesha, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 2019 (123), 5257-5265.

- R. Pariser and R.G. Parr, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1953 (21), 767-776.